But in matters like this, it takes a gavel and dark robe, not a song, to make serious changes. In 1978, the Supreme Court decided 5-4 in FCC v. Pacifica Foundation that the FCC could ban indecent material from broadcast airwaves between 6 a.m. and 10 p.m. The commission established this “safe-harbor” period in response to an angry father who wrote the commission after hearing George Carlin’s “Filthy Words” monologue on the radio while driving with his young son. According to the decision, TV and radio are “pervasive” enough to reach children, so the FCC has grounds to ban indecent content during hours when they’d normally be awake.

Fast forward 33 years. The Supreme Court has agreed to hear a case that could redefine how much authority the FCC has over TV and radio airwaves. Soon to be in question is whether the commission can punish broadcasters the first time they air a fleeting expletive — which is an unscripted, indecent word spoken once — on TV or radio. Below is a screen shot from a New York Times article about the case, called FCC v. Fox Television Stations:

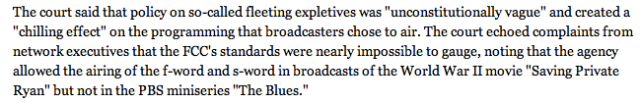

The Supreme Court ruled the FCC could punish broadcasters for airing a single fleeting expletive when it heard this same case in 2009. But the following year, the 2nd U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals disagreed. Here’s a screen shot from a Los Angeles Times story about its decision:

Next on the Supreme Court’s agenda, then, is an appeal by the FCC, which will try to prove its policy is not “unconstitutionally vague” and that it still protects viewers from indecency during safe-harbor hours.

Next on the Supreme Court’s agenda, then, is an appeal by the FCC, which will try to prove its policy is not “unconstitutionally vague” and that it still protects viewers from indecency during safe-harbor hours.If you’re like me, this is probably confusing. So, let’s take another route: rewind to 1978, and then fast forward again to 2011. But this time, think about your computer monitor, not your TV screen. While the Supreme Court prepares to decide what should be allowed on TV and the radio, here’s a look at what is allowed online.

Indecency

Should journalists be allowed to publish indecent material on the Web? Well, that’s actually a trick question because indecency is a term that only applies to broadcast media. Online, the word is obscenity.

Should journalists be allowed to publish indecent material on the Web? Well, that’s actually a trick question because indecency is a term that only applies to broadcast media. Online, the word is obscenity.Here’s a screen shot from the FCC website that defines this term. Obscenity is a step up from indecency, and it applies to both broadcast and Internet journalism:

The Supreme Court established this three-part test in Miller v. California. That decision, however, was in 1973. According to LegalZoom.com, the rapid growth of the Internet has made the definition of obscenity a bit fuzzy.

The Supreme Court established this three-part test in Miller v. California. That decision, however, was in 1973. According to LegalZoom.com, the rapid growth of the Internet has made the definition of obscenity a bit fuzzy.“The Miller Test is based on what is offensive in a certain community, not the United States as a whole,” according to the site. “For example, what’s offensive to someone from New York City may differ from what offends a person in Topeka, Kansas. But, the Miller Test’s basis of ‘community’ becomes blurred with the advent of the Internet; a state can define a community as the state as a whole, a county, a city or another geographic area.The geographic area of the Internet, however, is nonexistent.”

Perhaps the Supreme Court will have narrowed down an online interpretation of the Miller Test by the time I graduate from college (and have a job, of course).

Profanity

It all comes down to newsworthiness.

“Unless profanity can rise to the level of obscenity,” it’s not illegal for news organizations to publish it online, said Sandy Davidson, a Missouri School of Journalism associate professor who teaches media law.

But journalists shouldn’t quote profanities unless there’s a “compelling reason for them,” according to the 2010 Associated Press Stylebook.

The decision, it seems is largely up to news organizations. Steve Coll, former Washington Post managing editor, told the American Journalism Review in 2000 that the Post doesn’t publish words ‘that would be offensive to family readers of a newspaper unless that word is essential to the news or to the meaning of an important story, and reaching that judgment often involves a sense of the word’s offensiveness on the one hand and its importance on the other hand.’

Here’s another policy described in the same article:

There have also been debates about whether less offensive words, like “sucks,” should be allowed in news stories, according to the article.

Dead-body photos

National Public Radio last year published a photo on its home page of a man stepping over dead bodies in the aftermath of the Haitian earthquake. The decision drew both criticism and praise from website visitors.

Former NPR ombudsman Alicia Shepard wrote an article on the website in which she said there wasn’t enough “context” to justifiably put the photo on the home page.

“Without a caption the picture became a Rorschach test for the viewer,” she wrote.

Legally, journalists can publish photos of dead bodies. The decision is ultimately a balancing act between conveying a powerful message and potentially offending viewers.

Nude photos

Need I say newsworthiness again?

I wasn’t able to find a law that specifically outlined criteria making it OK for a journalist to publish a naked photo online. So, I presented the following scenario to Davidson: If a news organization wanted to publish a picture of a starving child online, and that child happened to be naked, would it be allowed?

She said she couldn’t answer the question with 100 percent confidence because it’s possible that child-pornography laws would prevent such a photo from running. But Davidson said she doesn’t think a picture of a starving Somali child would qualify as pornography.

Davidson said the iconic Vietnam War photo of a naked girl running from a napalm attack, taken by Associated Press photographer Nick Ut in 1972, could be used as a precedent for future decisions about the newsworthiness of nude photos.

What legal protections do journalists have?

If you’re a blogger and someone decides to post a libelous comment on your page, Section 230 of the 1996 Communications Decency Act has your back.

“No provider or user of an interactive computer service shall be treated as the publisher or speaker of any information provided by another information content provider,” according to the law.

Section 230 also applies to retweets. “If a journalist or news organization were to retweet a defamatory statement, they would not be held accountable. If, however, they added a defamatory remark as part of the retweet, they could be,” according to Poynter.

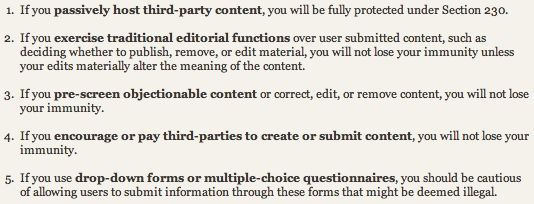

The screen shot below from the Citizen Media Law Project summarizes what you need to know about the act, which also

Did I miss anything? Let me know!

——————————————————————————-

——————————————————————————-

“Family Guy” screen shot taken from a YouTube video containing the FCC song.

FCC logo screen shot taken from the FCC website.

NPR logo screen shot taken from the NPR website.

No comments:

Post a Comment